How can we continue to live fully through unthinkable catastrophe?

Britt Wray, PhD, is one of the foremost thinkers in the climate psychology space. Her book is Generation Dread: Finding Purpose in an Age of Climate Anxiety, and she has recently launched what she calls a “Resource Hub” that offers a quiz with customized links to resources that can address feelings ranging from climate distress to anger to trauma to isolation for activists, educators, first responders, mental healthcare providers, parents, young people, survivors of climate disasters, and the general public.

Wray also maintains her blog: I particularly enjoyed “Dear Climate Therapist: What Should I Do with My White Hot Rage?” Guest blogger Caroline Hickman argues that anger isn’t the problem, but perhaps the solution if it motivates action. Hickman argues that we should feel all our feelings, and that furthermore, we should cultivate a healthy “emotional biodiversity…a rewilding of the psyche if you will.”

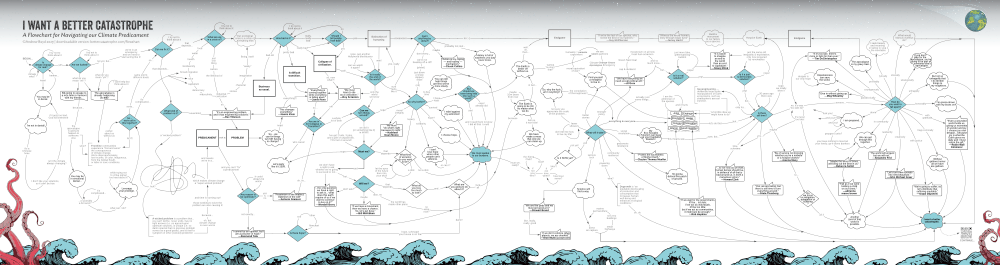

The resources on the hub I linked to are not a walk in the park, but then neither is processing climate change. First, I found Andrew Boyd’s I Want a Better Catastrophe, which equips people to endure and even find joy and gratitude during this excruciating moment – when everything we care about may soon be lost. As the mother of a terminally ill child, this reverberates.

Figure 1: Andrew Boyd’s Flowchart at https://flowchart.bettercatastrophe.com/

I was also referred to a book I’ve already read, David Wallace-Well’s The Uninhabitable Earth. From there, I tracked down Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, which approaches a question I have been centrally concerned with: how are we not comprehending how bad climate change will be and why are we not grasping at the solutions that exist? He assigns the dearth of effective fiction on climate change disaster to its uncanny aspect.

Given the luxury of time over the break, before my review comes in and revision begins, I read Boyd. Boyd sees despair as the way to pierce through denial. He says, therefore, that “despair is our only hope”:

As we stare into the darkening waters of climate catastrophe, the Serenity Prayer may not be able to get us over our grief (what could?), but with a modicum of courage and wisdom it may help us to carry that grief into battle.

I agree. And that was before the second Trump administration.

I also agree with Boyd’s proposition to resort to gallows humor. Often, I cannot help myself, as when I will share an especially grim fact with class, framed with comic understatement (litotes). I find myself laughing half-hysterically, on display before thirty rather bewildered looking undergrads, hoping simply to pull it together before laughter descends into outright sobbing: “Wait….ha, ha….I need a moment!”

Boyd says, “more than just a balm, gallows humor is an act of cosmic defiance, a reframing, a choice to tilt our gaze to see the human-all-too-human muck of things in a cosmic, tragicomic light.” He rejects light-hearted, frivolous laughs and calls instead for “The tragic laugh. The rueful, heartbroken, accursed laugh. The laugh that has all the sadness of the world in it, and still laughs.” Right there with you, brother. And I am glad I kept reading to the profounder message towards the end of his book.

Speaking with the philosopher Joanna Macy, he says, “you do the Work [That Reconnects] to help people become stronger, more resilient fighter for justice, and also good caretakers of each other in the here and now even if we’re going down.” The uncertainty about our future is in itself difficult to bear, as I well know. Even a vestige of hope heightens the agony of incipient loss.

When I am not scaring my students, I am trying to balance all the emotional valences that naturally surface when learning the bad news about climate change, loss of biodiversity, and increasing toxification of the biosphere—and us. I nearly always say something like, “I am so sorry to have to tell you this.” I am. Yet to remain silent is much worse, and often my students understand this. Often, they ask me why no one has ever shared these truths with them before—because whatever your parents’ political persuasions, doing your own high-quality research on any topic in global environmental health (and I let them choose) leads you to some dismal conclusions.

In addition, many of my students have some personal story of loss: personal diagnoses of cancer, Crohn’s disease, or endometriosis; siblings with autism, leukemia, and neurofibromatosis, attributed to exposure to Willowbrook’s Sterigenics; friends choking on wildfire smoke in California; homes, churches, and familiar landmarks lost to Hurricane Helene in North Carolina or Katrina in Mississippi; and friends dying of heat stroke during football practice. And this is a partial sampling from one semester.

The best feature of Boyd’s project is a flowchart that outlines the entire logical thought process of his conclusions, which is that we must fight for a “better catastrophe.”

As for Unthinkable Resources Hub, I am just beginning to plumb its depths, but found my first foray into it truly helpful and thought-provoking. I particularly recommend it for anyone actively wrestling with the dire predictions of climate change in hopes of finding a nuanced approach to the hope-despair dichotomy. Because of the choices people have made for the last fifty years, and the choices we all continue to make daily, catastrophes of some ilk are now undeniably upon us.

References

Andrew Boyd. (2023). I Want a Better Catastrophe: Navigating the Climate Crisis with Grief, Hope, and Gallows Humor. New Society Publishers.